子ども達のレジリエンス

CHILDREN’S RESILIENCE

復興を志す08

震災後の「あたりまえ」は、復興の軌跡

The “norm”after the disaster is the trail of recovery.

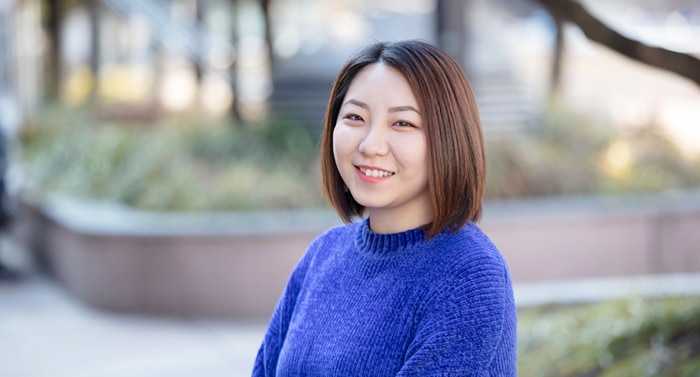

岡部 由梨子 | 福島県浅川町

Yuriko Okabe (Asaka, Fukushima)

それぞれ違う震災の記憶

Support Our Kidsのプログラムに参加したことで、東日本大震災と郷土について考える大きなきっかけになりました。プログラム期間中、ホストファミリーや、友人、大使館等訪れた先々で、何度も震災について聞かれることがありました。

「どんな感じだったの?」「家族や福島は大丈夫だった?」「今はどうなっているの?」など、震災当時のことや現状について聞かれたとき、私はあまり答えることができませんでした。英語で説明するのが難しかったことや、積極的に話し出す性格ではなかったこともありますが、「あまり知らなかった」というのが、正直一番大きな要因であったと思います。

私が住んでいた福島県の県南地域では、津波もなく、原子力発電所からも遠かったので、震災の被害は大きくありませんでした。福島に住んでいたというだけで、体験したような、知った気になっていましたが、実際は原発の現状や、自分が生活している以外の地域の被害や復興の状況ついて、あまり知らなかったことを痛感しました。

プログラムに参加したメンバーはさまざまな被災地から来ており、それぞれに震災の記憶があって、それを取り巻く現状や感情、必要としている支援や抱く希望は、人それぞれ違っていたのだと思い、自らの視野の狭さを実感しました。

また、プログラムを通してたくさんの人と出会い、様々な感情に触れる機会を積み重ね、周りのこと、自分のことについて、再度考えることが増えました。特に、プログラムで出会う方々は、今まで出会うことのなかった人たちばかりで、交流することで自分の中の価値観や感情が深みを持っていくような感覚がありました。

帰国後は、今まで以上に世界に目を向けるようになり、自己実現していくために、物事に積極的に取り組むようになりました。そして、いろんな場所でいろんな人と話したり、意見を交えたりする中で、自分のすべきことや進むべき道が見えてきた気がします。

また、いわき地区や石巻地区といった地元以外の被災地を訪れてみたり、大学進学を機に講義やサークル活動を通して、震災や復興について学ぶ機会を積極的に設けるようにもなりました。

復興の形は1つではない

進学先の岩手県も震災で甚大な被害を受けました。在学している岩手大学では、入学してすぐ、1年生全員を対象に震災学習が行われています。私もその一環で、三陸鉄道の『震災学習列車』に乗車しました。震災学習列車では、三陸鉄道に乗車して、震災や復興の状況や震災の記憶を直接見たり聞いたりしながら、被災地の現状を学ぶことができます。

震災学習列車の車窓から見た南三陸には、「何もない」景色が広がっていました。震災直後は津波の影響で、がれきが広がっていたそうです。復旧活動により、がれきは撤去された一方で、人が住んだり、産業が発展できたりするようなインフラや設備はまだ整っていませんでした。この震災学習を通して、地元である福島県と、岩手県の両方の被災地の現状を目にしたことは、私にとって、とても衝撃的な体験となりました。

福島県では「震災」というと、原発事故による被害という印象が大きいです。原子力発電所は廃炉に向けて多くの人が尽力しているものの、震災から10年となる今でも多くの課題があります。加えて、原発周辺地域に立ち入れず仮設住宅で暮らしていたり、農林水産物や人に向けられた風評被害に精神的に追い詰められてしまったりと、人々の不安を少しずつでも取り除いていく対策も講じられてきたように思います。

一方で岩手県では、震災後に襲ってきた大津波により、たくさんの人やものが一瞬にして奪われました。そんな岩手県では、3.11のことを「東日本大震災津波」と称し、奪われた街並みを取り戻す復旧活動のみでなく、震災や津波の記憶を風化させないために、未来に伝承・発信していくことをあわせた復興活動を行っているように思います。

私は、大学の研究活動の一環で沿岸地域に赴き、津波により塩害を受けた地域で、作物を育てる活動に関わったり、サークル活動で、農業体験を通して地域活性に尽力を注ぐ農家の方と協力したりする中で、田舎の良さを再認識しつつも、地域活性の難しさも体験しました。

また、学童保育のアルバイトの中で、今の小学生のほとんどが震災を経験していないことを実感し、震災の記憶を次世代に受け継いでいくことも必要だと強く思いました。

福島県、岩手県の両県に身を置いたことで、3.11の被害やその後の復興の形が1つではないことを、あらためて感じています。

震災後の「あたりまえ」

先日、東海地方出身の友達といわき地区に旅行する機会がありました。常磐自動車道や町中にある放射線量を表示するモニターを見た友人に、「このモニターはなに?初めて見た」と尋ねられました。それは、私がはじめて、自分にとっては「復興」が身近にありすぎて、感じることができなかったものだと実感した瞬間でした。

原発事故後、福島県では、公園や学校、路上など至る所に線量計が設置されました。福島で過ごしてきた私にとって、震災のせいで設置された線量計は日常の一部となっていたのです。他にも、農作物や飲料水が放射性物質モニタリングされていたり、定期的に甲状腺検査を受けていたりなど、私たちが安心安全な日常を送るために、震災後「あたりまえ」になったものは身近に多くあると思います。この、他県民からみれば奇妙であるような「あたりまえ」は、復興の軌跡ともいえるのではないかと思います。

一方で、未だに原発周辺は立ち入り禁止区域であり、仮設住宅で暮らす人もいらっしゃいます。避難指示の一部は解除され、一部住民は帰還しているものの、長い避難生活を経て、「もう故郷に戻らない、戻れない」元住民も多いのが現状です。

さらに、震災後の避難生活による体調悪化、自殺などによる「震災関連死」でも沢山の命が失われました。震災で家が倒壊したり、津波で家族を亡くしたり、原発爆発により家や病院から避難したことで十分な医療が整わずに亡くなってしまったり、風評被害により心に傷を負ったりした人が沢山いました。

震災から10年経った現在、災害復旧工事に関してはほぼ全てが完了し、除染特別区域を除く除染実施状況に関しても全てを終了しています。風評被害を受けた農林水産業も厳しいチェックが行われ、放射能による汚染がほとんどない安全な食べ物ばかりであることが証明されていることで市場が回復し、震災前と同様な水準にまで回復しており、着実に復興の道を歩んでいます。

さらには、東日本大震災及び原子力災害によって失われた浜通り地域を、新たな産業基盤の構築や人材育成の場とする『福島イノベーション・コースト構想』も進行しており、震災前以上に活気のある福島の未来作りも進んでいます。

子どもたちの未来を開く

Support Our Kidsに参加した当時、私は高校1年生で、ぼんやりとではありましたが、将来は農業に携わりたいと考えていました。また、幼いころから長期休みなどを利用して、柿農家の祖父母の仕事の手伝いをしていましたが、私の親兄弟は後を継がなかったため、農業の後継者不足という課題も常々感じていました。

ですから、今後の進路として農学部に進学し、好きだった生物のしくみや農業の技術課題について学びたいと思っていました。そして将来は農家ではなくても、なにかしら農業に関わることで、農産業の振興や発展に関わっていけるような将来を思い描いていました。

現在の私は、当時の目標通り、農学部に進学、その後、大学院に進学して、植物について学びながら、果樹生産の課題を解決するための研究を行っています。

大学院卒業後は、地元の福島県で農業高校の教員として働き、地元の福島県の教育という現場から、農産業の発展や地域振興に関わっていきたいと考えています。

これまでに福島、岩手で経験したこと、学んだこと、感じたことを次の世代に伝え、これからは子どもたちの未来を開く手助けになるような機会を提供することで、今まで支援していただいた恩返しをしていきたいと思います。

Different disaster memories

Participating in the Support Our Kids program was a great opportunity for me to think and contemplate about the Great East Japan Earthquake and my hometown.

During the program, I was asked many times about the disaster by my host family, friends, and people in the embassy.

"What was it like?

"Is your family and Fukushima okay?

"What's going on there now?”

I was not able to answer any of those questions about the current situation. It was difficult for me to explain in English, and I am not an outgoing person. But to be honest, the biggest reason was that I did not know much.

In the southern part of Fukushima prefecture where I lived, there was no tsunami and we were far away from the nuclear power plant, so the damage from the earthquake was not serious. Just because I lived there made me looked like as if I had experienced and knew about it, but in reality, I did not know much about the current situation of the nuclear power plants, the severity of the damage, and the reconstruction of areas other than where I lived.

The program members came from different disaster-stricken areas, and each of them had their own memories of the disaster. I realized that the current situation and emotions surrounding the disaster, the support they needed, and the hopes they had were all different from each other, which made me think how narrow-minded I was.

Also, through the program, I met many people and had many opportunities to experience various sentiments, which made me think again about my surroundings and myself. I had never met them before, and I felt as if my sense of values and emotions were deepened by interacting with them.

After returning to Japan, I look at the world differently than before and started to actively work on things to achieve self-realization. Through talking and exchanging ideas with various people in various places, I was able to realize what I should do and what path to take.

In addition, I visited disaster-stricken areas outside my hometown, like Iwaki and Ishinomaki. And when I was in university, I actively took opportunities to learn about the disaster and reconstruction through lectures and club activities.

There are many forms of reconstruction

Iwate prefecture also suffered tremendous damage from the earthquake.

At Iwate University, where I am currently studying, an earthquake disaster study program was held for all fresh men immediately upon enrollment.

As part of the program, I took a ride on the Sanriku Railway's "Earthquake Learning Train". Students can learn about the current situation of the disaster-stricken areas inside the train, directly see the progress of the reconstruction, and listen to memories of the disaster.

There was nothing to see when I viewed Minamisanriku town from the train window. Immediately after the earthquake, there were lots of debris from the tsunami. While it has already been cleared away, infrastructures and facilities were not yet in place for people to live or for the industry to develop. It was a shocking experience for me to see the current state of the disaster-stricken areas in both Fukushima and Iwate prefectures through the trip.

In Fukushima, the word "earthquake" is often associated with the damage caused by the nuclear power plant explosion. Many people are working hard to decommission the nuclear power plants, but even now, 10 years after the disaster, there are still many problems to be solved. But it seems that measures have been taken to gradually alleviate the anxiety of people who are unable to enter the areas around the nuclear power plants, people who are living in temporary housing, and those who are mentally trapped by rumors and stigmas about agriculture, forestry, and marine products, and people.

On the other hand, in Iwate, the tsunami that came after the earthquake took away many lives and things in an instant. There, March 11 was referred to as the "Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami". Not only are people working to restore back the townscape that was lost, but also passing on and preserving the memories of the disaster for it not to be forgotten.

As part of my university research activities, I went to the coastal areas and was involved in activities in growing crops in areas destroyed by the tsunami.

In addition, while working part-time in a childcare center for school children, I realized that most of today's elementary school children are not aware of the earthquake, and I strongly believe that it is necessary to pass on the memories about it to the next generation.

Having spent time in both Fukushima and Iwate reminds me that reconstruction has many forms and is not limited only to one style.

The norm after the disaster

I was able to have a chance to travel to Iwaki area in Fukushima together with a friend from the Tokai region. When she saw the monitors displaying radiation levels along the Joban Expressway and other parts of the town, she asked me what were those things and that she had never seen one before. It was the moment when I realized, for the first time, that the reconstruction was something I was so accustomed to already that I didn’t feel it anymore.

After the nuclear accident, dosimeters were installed everywhere in Fukushima, including parks, schools, and on the streets. For me, having lived in Fukushima, the dosimeters became a part of my daily life. There were many other things around us that have become "natural" after the disaster to help us lead a safe and secure life, such as radioactive monitoring of crops and potable water, and regular thyroid checkups. This "norm" which may seem strange to the people from other prefectures, can be seen as the trail of recovery.

On the other hand, the area around the nuclear power plant is still off limits, and there are still people living in temporary housing. Although some of the evacuation orders have been lifted and some residents have returned to their hometowns, there are still many former residents who will not or cannot return to their homes after the long evacuation.

In addition, many lives were lost due to "disaster related deaths" like suicide and health deterioration after the evacuation. People lost their homes and families due to the earthquake in the tsunami that followed. Also many people who evacuated from their homes and hospitals died because they were unable to receive adequate medical care due to the nuclear plant explosion, and others suffered psychological trauma caused by harmful stigmas.

Now, 10 years after the disaster, almost all of the disaster recovery work has been completed. The decontamination work has also been completed except in the special decontamination zone. The agriculture, forestry, and fishery industries, which had suffered from misconceptions, have been subjected to strict checks, and the market has recovered to the same level as before, as it has been proven that the products are safe and free from radioactive contamination.

Furthermore, the Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework, which aims to turn the totally devastated Hamadori region into a place for building a new industrial base and fostering human resources, is already underway, and the future of Fukushima will be more vibrant than ever.

Opening up the future for children

I was in my first year in senior high school when I participated in the Support Our Kids program when I somewhat had the idea of working in the field of agriculture in the future. I had been helping my grandparents, who were persimmon farmers, with their work during long vacations since I was a child. And since my parents and siblings did not take over, I always felt that there was a shortage of successors.

It made me want to study agriculture to learn about the mechanisms of living things and the technical issues of agriculture, which I loved. Even if I would not become a farmer, I wanted to work at least in agriculture related activities in promoting and developing the industry.

As I had set out to do at the time, I went on to study at the Faculty of Agriculture, and later in graduate school, where I am conducting research to solve problems in fruit tree production while learning about plants.

After graduate school, I would like to work as an agricultural high school teacher in my hometown in Fukushima and be involved in the development of the agricultural industry and regional development.

I would like to pass on to the next generation what I have experienced, learned, and felt in Fukushima and Iwate. In the future, I would like to repay the support I have received by providing opportunities that will help open up the future for children.

RESILIENCE

復興を志す

復興を志す 01

自分が次の世代に、この美味しさを残す。ファーマーそして農チューバーという挑戦。

復興を志す 02

海外で得た「福島プライド」を、未来を担う子どもたちに伝えたい、育てたい。

復興を志す 03

教える立場になった今、一番大切にしていること。「心を理解しようとすること」

復興を志す 04

ドバイから、世界に通用する福島出身の日本人になりたい。

復興を志す 05

命が助かったからには、少しでも復興に役立つ大人になりたい

復興を志す 06

大人になった私が、今度は、地元・栗原の子ども達を応援したい

復興を志す 07

『恩送り』という、恩返しのカタチ。

復興を志す 08

震災後の「あたりまえ」は、復興の軌跡

復興を志す 09